Shifting from Power to Collaboration: Realizing the Vision of Shared Governance

A new education playbook is emerging as we approach year two of the pandemic. In our last post, we spoke about the pandemic as both an accelerant and revealer of the underlying dysfunction in institutional culture. The pandemic has also raised awareness and commitment to addressing issues previously paid lip service to. This commitment manifests itself in budgeting for DEI initiatives that support faculty, students, and administrators, addressing mental health for a broad spectrum of employees, and doubling down on a commitment to research, discovery, and innovation, increasingly under attack across our broader culture.

How we navigate these emerging commitments is influenced by shared governance, a model for decision-making across all higher education institutions. There is much written about this model of authority being delegated from the board to administration, and then from administration to the academy. In a perfect world, the Board oversees and guides, the administration develops tangible strategies to fund and execute, and the academy provides the intellectual rigor and evidence that validates the strategy. Each body offers complementary value to strategic initiatives, such as innovating on academic offerings, integrating non-traditional academic delivery, or addressing other student or research needs.

Missing in the literature on shared governance is a recognition that in the absence of collaboration, these groups execute by power over people or activities. Breakdowns of trust, lack of transparency, or an incomplete understanding of roles end up driving boards, administrators, and academics to act in unproductive manners. This form of unhealthy tension leads these groups to shift from a “we’re on one team” mindset to focusing on controlling what each think is under their own authority.

Former Provost Linda McMillan writes about this unhealthy tension. “We do not often perceive ourselves to be collaborators. Frequently we encounter each other as adversaries-bound to represent our distinctive groups and monitor the behavior of the other side."

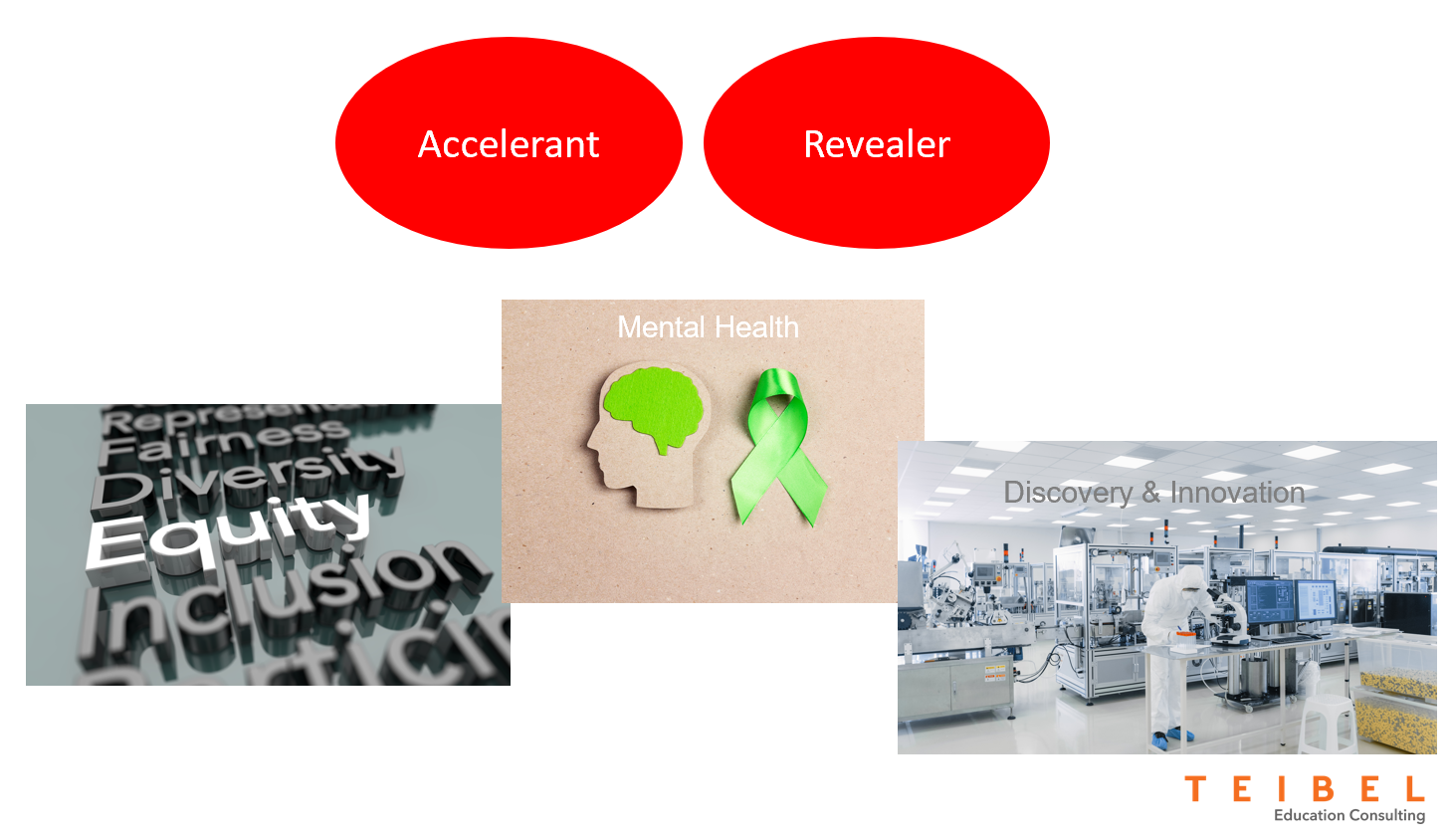

When we monitor other’s behavior, the most effective way to get things done is through power - recognized authority that “tells” others what to do or ignore what’s being asked. A strategic initiative such as integrating online education or restructuring departments then becomes an exercise of who has control over what. The academy will exercise power over cooperation or engagement, administrators will either provide or deny resources, and Boards exercise power over their presidents or chancellors to keep the peace. This is a low level of partnership.

This chart lays out how we often think about each other in these different roles.

Navigating this problem is simple, but not easy. Start by recognizing and naming these interpersonal dynamics, not from a place of blame but from a recognition that this is the result of diminished trust. Then, open conversations to learn about one another. Ask the question of other groups - “What concerns do you have that you’d like us to appreciate?” Then listen. This straightforward yet powerful question is the gateway to building an understanding and appreciation for what others are dealing with and begins to form a roadmap for the healthy tension of shared governance that we all strive for.

To learn how we can help you and your institution develop a culture of trust and collaboration, visit us online at teibelinc.com.