Howard Teibel, Teibel Education Consulting

Sara Walsh, Brown University School of Public Health

Leadership is about exercising power, but not as force or domination. We increase our personal power by engaging authentically with others in the mission while exercising the authority we’ve been granted to improve outcomes. What allows some to lean in and make unpopular decisions? These include restructurings, reducing programs, and moving on from those who are not performing up to the standards to get the job done. Making difficult decisions is hard, and for good reason – calls of no confidence, misuse or misunderstanding of shared governance, or sometimes, simply caring too much about being liked by the people you need to lead. Provosts, Chief Business Officers, and other senior leaders face the same obstacle when attempting to make changes too fast.

Central to being effective in higher education is learning to navigate the culture of shared governance and understanding both its strengths and its limits.

A Brief History

The effective practice of shared governance is ultimately the mechanism that strengthens our institutions’ ability to get things done. In 1920, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) described shared governance as “emphasizing the importance of faculty involvement in personnel decisions, selection of administrators, preparation of the budget, and determination of educational policies.”

Tim Austin, former Provost and Vice President of Academic Affairs at Duquesne University, notes, “at the time of that first big description of shared governance, almost every large institution was one quarter of the size it is today. What we have now is a model designed for a different world. So much has changed—the speed of decision making, regulatory complexity, financial challenges, high-tech enrollment strategies and IT embedded in every organizational effort. Shared governance was much easier as a mechanism when smaller numbers of people were handling a much simpler organization.”

With this dramatic shift of size and complexity, it is no wonder tensions around how decisions should be made are more present than ever.

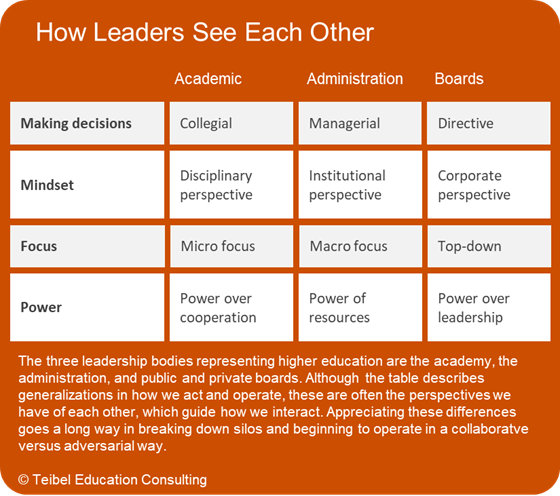

This brings us to an important distinction. The academy, administration, and boards each speak a different language. Faculty have a deep appreciation for the discipline of argument (to claim, to ground, and to warrant). Central to academic culture is being collegial, and simply that dialogue is the point. Administrators, on the other hand, often speak a narrow language of “do.” Most everything is a problem to be solved, and speed is of the essence. No time for talk, only action. Our boards are all about the “why”. They care about perception and want as little public controversy as possible.

In theory, boards delegate authority to the president. The president delegates to their Provost and Chief Business Officer, who then delegate to the chairs, faculty, and administrators. When push comes to shove, the academy exercises control over engagement and cooperation, administrators exercise control over distribution of resources, and boards exercise control over their leaders. In the absence of having shared agreement and clarity of these roles, it’s all about control. And people suffer.

Another dimension of these relationships is summed up perfectly by Linda McMillan, former Provost at Susquehanna University:

“Faculty and administrators in most universities come together daily to accomplish a variety of tasks. However, we do not often perceive ourselves to be ‘collaborators.’ Frequently, we encounter each other as adversaries, bound to represent our distinctive groups and monitor the behavior of the ‘other side.’ Thus, we focus on negotiating compromise rather than on collaborating to create the most effective solutions.”

Whether myth, fact, or partial truth, collaborating “across the aisle” is difficult because it means taking the time to understand the needs and concerns of those working in different functional areas – and appreciating their contribution to the underlying mission.

George Martin, president of St. Edwards University, Austin, puts it succinctly:

“Honoring shared governance is about reminding all of us that the board has primary authority and part of its role is to delegate important matters of university life to faculty and senior leadership. There is nothing I can think of in university life that does not involve faculty and staff input.”

Here is the key to his wisdom: While everyone has a voice, only some have a vote, and even fewer should have the ability to veto.

Shifting from Consensus to Commitment Management

Too often the goal is described as building consensus. This is wrong. Consensus is a means to an end. Once we’ve identified the right people to be on your bus, the next step is to teach them a common language.

Sara Walsh, Executive Dean of Finance and Administration at the Brown University School of Public Health, is leading her sixty- person organization to build this culture of commitment. “We are focusing on ensuring not just that our senior leaders are connected to the vision, but ensuring the message and skills reach every person in our organization,” says Walsh. “This shift requires getting everyone’s voice in the conversation, and teaching people to learn new skills in coordination, commitment management, and cultivating productive mood.”

Additional Actions We Can Take

A principle or theory is only as good as our ability to put it into practice. In this complex decision-making structure, we need to learn how to engage and then decide. A critical question to consider is how to ensure you’re keeping your energy on the folks who will go with you. Consider carefully these three distinct groups:

My change agents, who can advocate better than me on this idea.

The folks who can be difficult because they ask tough questions but, in the end, will be contributory.

Those who may have a loud voice, but that we need to respectfully ignore.

Watch this short animation on Placing Our Energy that describes how to keep your focus in a productive place.

A positive shared governance experience is possible, although it requires authentic communication, rising above politics, and getting groups that speak a different language to come together and appreciate each other’s contribution.

Shared governance asks difficult questions about who is responsible, who should be involved in conversation, and how the institution ensures they don’t get bogged down in endless debate. The model has great strengths when administered with transparency, good will, and a willingness to make tough decisions. The bigger question for all of us is “can we lead with humility while exercising the authority to move our culture forward with resolve.”

Reach out to us:

To learn more about how to build a culture of commitment in your organization, reach out to us at info@teibelinc.com.